On Tuesday, January 28, we traveled to Pergamino to carry out a workshop on the design of maize observation variables for collaborative breeding, together with a dream team of breeders and producers. Among the breeders was Daniel Presello, from INTA Pergamino, and Gustavo Schrauf and Pablo Rush, researchers of University of Buenos Aires. Among the producers, Enrico Cresta (member of the Argentine Movement for Organic Production, MAPO), Claudio Demo (also a professor at the National University of Córdoba), Milton Vélez and Sergio Toletti (member of the national network of counties and communities that promote the agroecology, RENAMA), from Río Cuarto, Córdoba; all of them work their seeds until blurring the line that separates the breeding production.

The goal of the workshop was to share what are the traits that are taken into account to evaluate and select maize plants and seeds, both from the points of view of those who make plant improvement and from those of those who produce. This collaborative work allows a better construction of the Bioleft platform field notebook, to reveal data that is then useful information for participatory improvement. To that end, twelve people traveled from south and north to meet at the offices of INTA Pergamino.

What to breed and what for?

After a brief introduction to Bioleft, we started the day thinking about the sense of working towards participatory breeding, particularly in a crop as central as maize. Enrico Cresta opened the game from the organic perspective: “The first response would be to have a maize material free of genetic modifications that has an acceptable yield with respect to a witness and that is the most practical to breed participatively, between producers and public entities. You can upload data and see traceability, how your seeds impacted elsewhere. ” Then he added: “We have to achieve something related with productive sovereignty. Material that we can handle if we have to resort to outside technology. Breeding through our tools.”

It is a common place that hybrid seeds always have better yield than varieties. Gustavo Schrauf, chair of Genetics of the Faculty of Agronomy of the University of Buenos Aires, put several questions on the table: “Do we breed a population or generate hybrids and evaluate hybrids? The tasks will be different and the ways of work too. They say ‘you can’t beat the hybrid’, you give up some productivity for that. But if producers have access to those lines and know how to breed, it’s a qualitative leap in that breeding. ” And he concluded: “The investment that was made in hybrid breeding is much greater than the other. Before it was 20% hybrid-variety and now it is 30%. What component of the yield is what makes the difference?”

Draw the supermaize

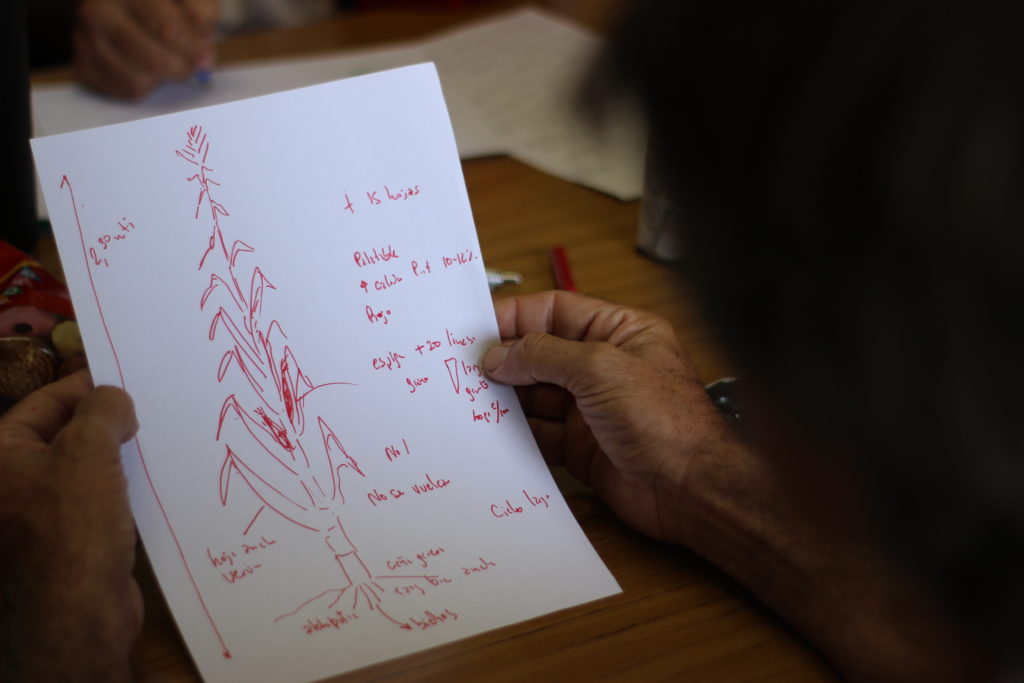

After the initial discussion, we started to co-design of observation variables, through a playful exercise. The plan was to imagine a super maize: the ideal maize for each one, with their corresponding super powers. Then, with paper and colored markers, draw it and describe it.

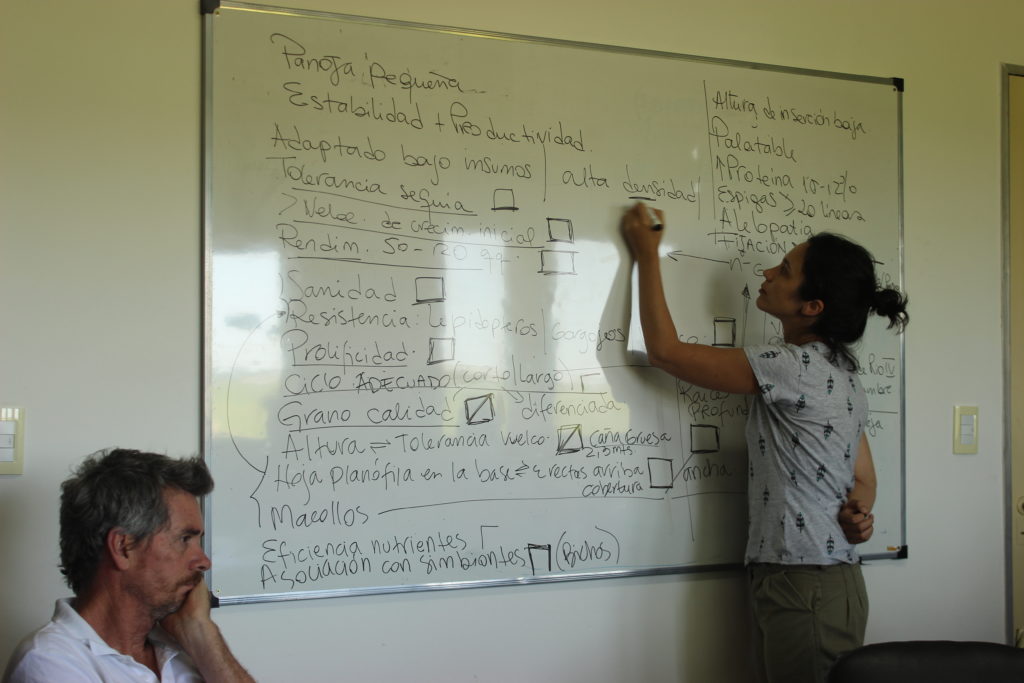

As drawings of tall and strong maize appeared on the paper, the elements that each participant takes into account when selecting seeds were also decanted. After a while, it was possible to list more than thirty features on the board. The ones that were repeated most were the height of the plant, the tolerance to overturn and breakage, the tolerance to drought and the differentiating characteristics of the grain (for example, color), the yield and the health.

After a round of conversations and sharing, the group agreed to define the six main variables in these terms: “resistance to overturning and broken”, “high initial growth”, “stability and productivity (performance)”, “spike health” , “quality of grain”, “low susceptibility to the Río Cuarto disease”. It was agreed to continue the joint work remotely and to arrange an upcoming meeting from March, to deepen the development of these common observation protocols.

This workshop is part of the three experiments that Bioleft carries out in the framework of the project supported by the Conservation, Food and Health Foundation, in which seeds of breeders are transferred from public institutions to producers and their performance is tested collaboratively, creating relevant information in the process. The information provided by the participants is extremely valuable, as it helps to improve the tools that Bioleft offers to the community to encourage participatory breeding. With these tools, we hope to help those who work in low-input agriculture get the right seeds for each crop.